With one in three French-speaking Belgian teachers considering leaving the profession, as shown by research conducted by the University of Mons, education unions have called for action on 10 February, not only because of the COVID-19 pandemic that is disrupting the school system, but also because there are many issues affecting education and its workers that remain unresolved.

This is not a formal strike call, but teachers who take part in the action, a rally in front of the seat of government of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation, will be covered by their trade union organisation. School administrative and blue-collar workers are also invited to participate. About 10,000 people answered the call and gathered in front of the headquarters of the Government of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation. A mobilisation of such magnitude is exceptional, the last of this type having taken place 11 years ago.

These French-speaking education workers have the support of their Flemish and German-speaking Belgian counterparts.

In the run-up to 10 February, work stoppages of less than 50 minutes were organised in a common front in schools during the week of 31 January. They were used to hold information meetings.

Efforts to cope during the health crisis unrecognised

“All the teaching staff have made a huge effort so far,” confirms Jean-Francois Lankester, communications officer for the CGSP Enseignement union. “All the more so during the last two years, in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, when everyone has shown exemplary adaptability in the face of the difficulties on the ground. In spite of this, they have not had any real recognition, nor have there been any measures that are fit to effectively combat the shortages.”

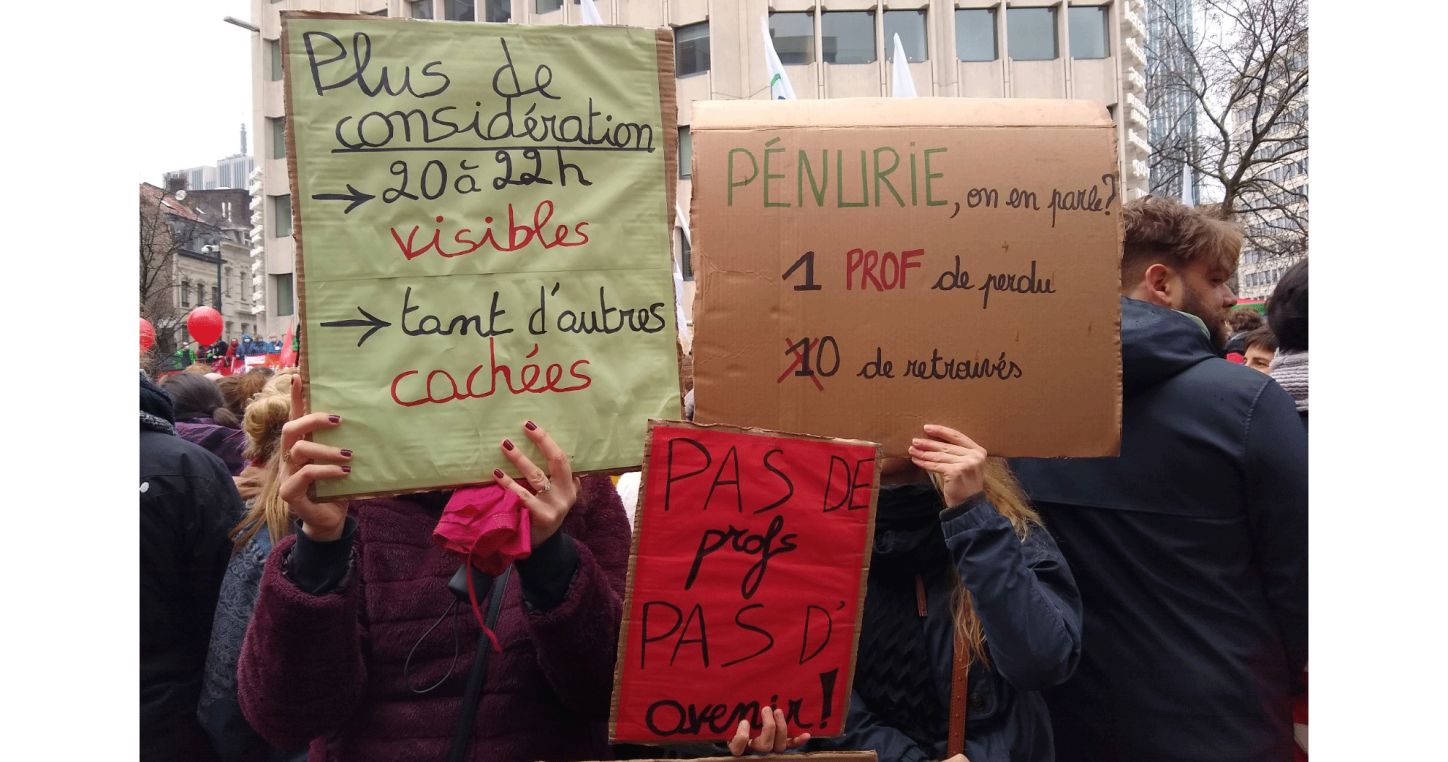

He also maintains that “the shortage of teachers is well documented, but political considerations do not encourage young people to enter or remain in the profession”.

Educators are still waiting for better working conditions and the upgrading of their profession

The communiqué of the common trade union front for education, extended to administrative, blue collar and university staff, states: “We have not had any concrete proposals in response to the list of demands submitted last April. The feeble proposals envisaged mainly refer to points in past agreements that have not yet been implemented. And on top of that, the government's intention is to extend the period of sectoral negotiations from two to four years. This is nothing less than a move to break the two-year bargaining cycle and it’s a violation of the law. Education support staff, “who are also essential, have been waiting for a long time for a salary increase and permanent contracts”.

The unions also denounce “an ever-increasing administrative overload, class sizes that are too large, preventing them from providing adequate support to pupils in difficulty, and a state of crisis management that is exhausting the staff [...]. The latter are working in deteriorating conditions”.

Moreover, they note that the crisis “has turned the spotlight onto the dilapidation of school buildings and the glaring lack of digital equipment”.

Concerning the Pact for Excellence in Teaching, which was intended to be “a systemic response to all the problems”, they say that it is now being implemented “in a totally unbalanced way”.

They conclude: “Faced with general indifference, the staff of educational institutions were put in a dangerous situation during the pandemic to allow the economic world to keep going. If education is really essential, it is time to prove it!”

Stumbling blocks for the unions

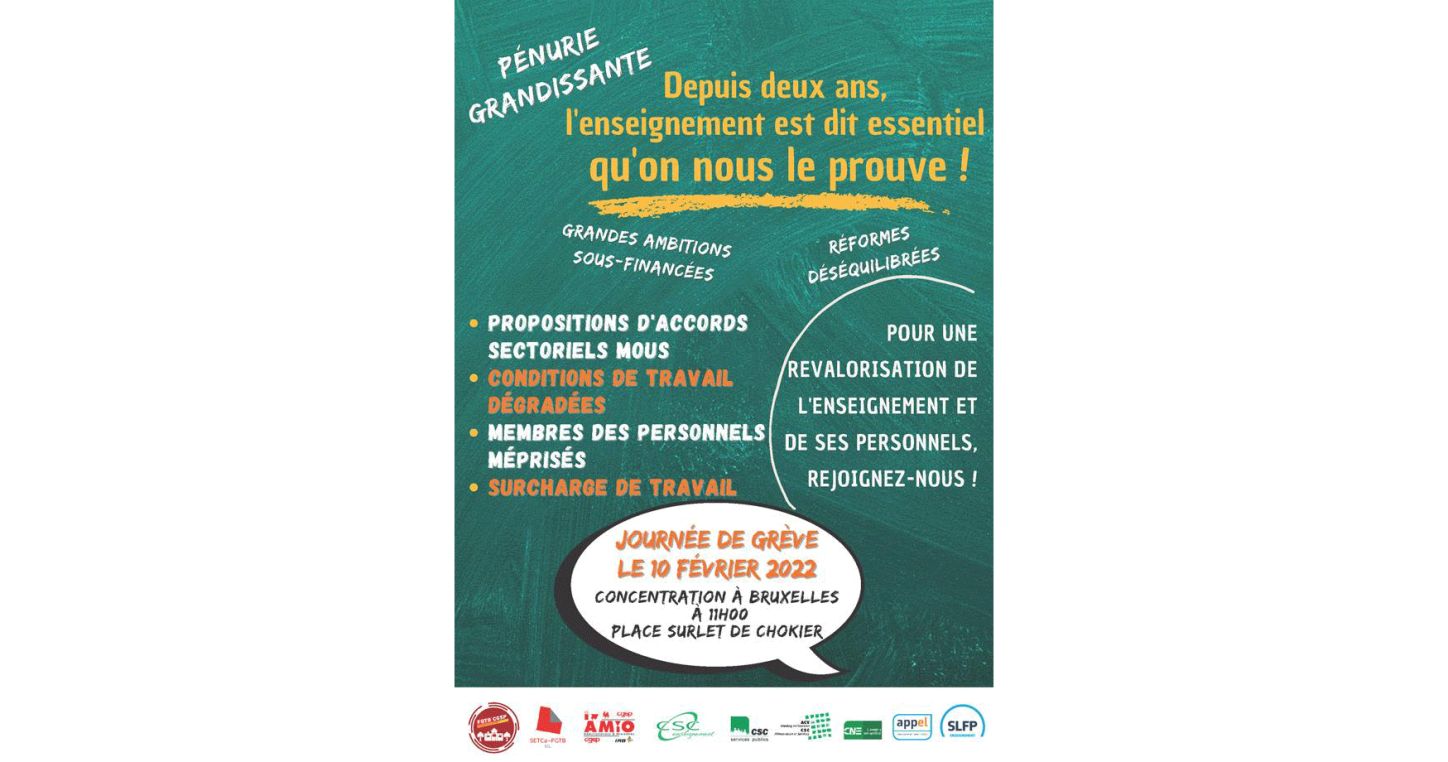

The unions condemn in particular:

- Weak or inconsistent sectoral agreements.

- An ongoing sectoral negotiation process that has not resulted in sufficient protocol proposals.

- The fact that no concrete proposals have yet been made in response to the list of demands submitted last April.

- The fact that there is no plan for the many points of past agreements that have been reached but not yet implemented.

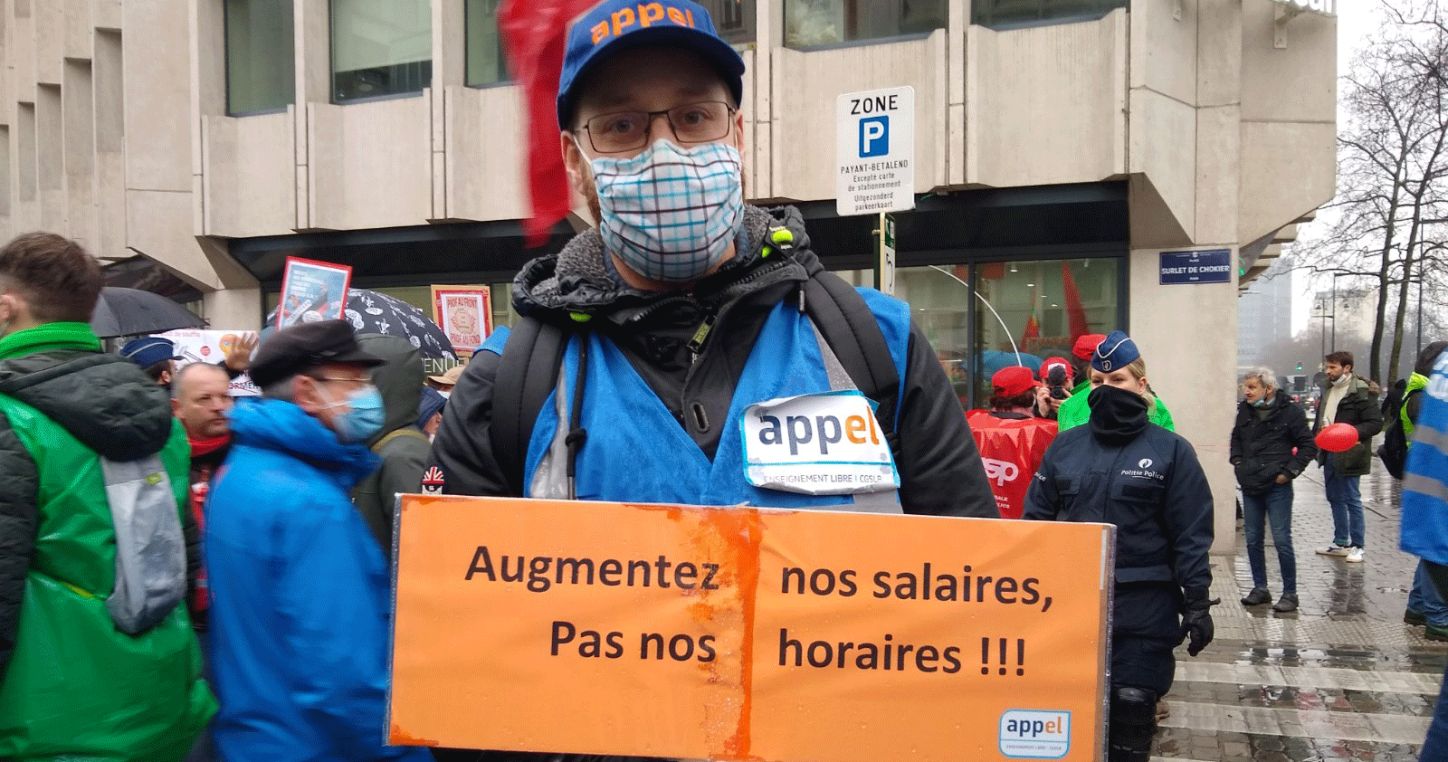

- Deteriorating working conditions. In particular: a working environment that leaves much to be desired, with the state of school buildings more than worrying; the chaotic move to hybrid teaching, with almost non-existent support measures (notably training) for distance learning; the new practices brought about by digital technology leave little right to disconnect because they no longer respect the boundary between private and working life, adding to the workload; the use of one's own private digital equipment despite all the risks this entails; the class sizes decree was a step forward, but they must be reduced further and the many derogations must stop.

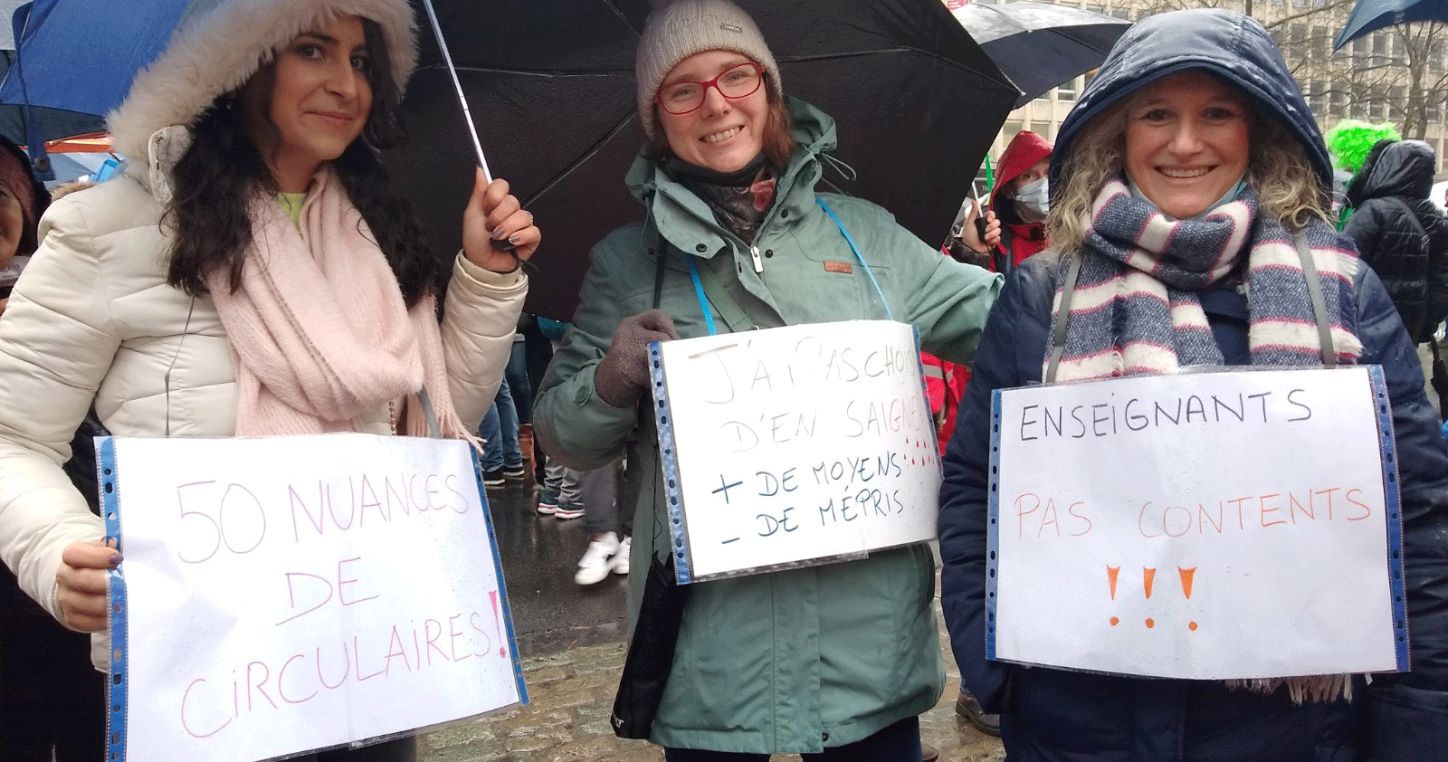

- Staff members treated with contempt. School staff were put in a dangerous situation during the pandemic in order to keep the economic world running. Despite this, in the media, the Minister-President of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation, Pierre-Yves Jeholet, reiterated comments that showed a total lack of consideration for these staff members by making comparisons between the private and public sectors.

- Work overload. This overload is linked to: an exponential increase in ‘administrative’ procedures; class sizes that are too large, making it impossible to provide adequate support for pupils in difficulty; increased cleaning and disinfection due to the COVID-19 crisis; tracing carried out by educational support staff; and boarding school staff who are neglected and devalued.

- Great but underfunded ambitions and unbalanced reforms. Given the state of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation's finances, the resources allocated to the various reforms that have been initiated since the introduction of the Pact for Excellence in Teaching are not sufficient to ensure efficient implementation. For the unions, spacing out the reforms would have been wiser in terms of getting to understand the reforms, the work overload as well as in budgetary terms.

Education must be genuinely treated as “essential”

Noting that “for more than two years now, at every opportunity and especially at the end of the consultation committees on the evolution of the health crisis, political figures from all parties have been repeating to us that education is an essential sector” Roland Lahaye, Secretary General of the Confédération des syndicats chrétiens de Belgique-Enseignement (CSC-Enseignement), points out “We didn’t have to wait for a health crisis to know this. Not only is this sector essential, it is a sector in which we must invest because it is an asset for society.”

While he indicates that “budgets have been made available to deal with the impacts of COVID-19 in schools”, he deeply regrets that “we are far from the set of demands tabled by the common front, which focused on tackling shortages”.

For him, “the essential need to stay on course [with the reforms and measures] has been compromised. It is time to react if we want schooling to return to its real meaning”.

In conclusion, he believes that “politicians have talked enough, they must now put their money where their mouth is”, and, addressing education staff, that “this is the opportunity to show your discontent”.