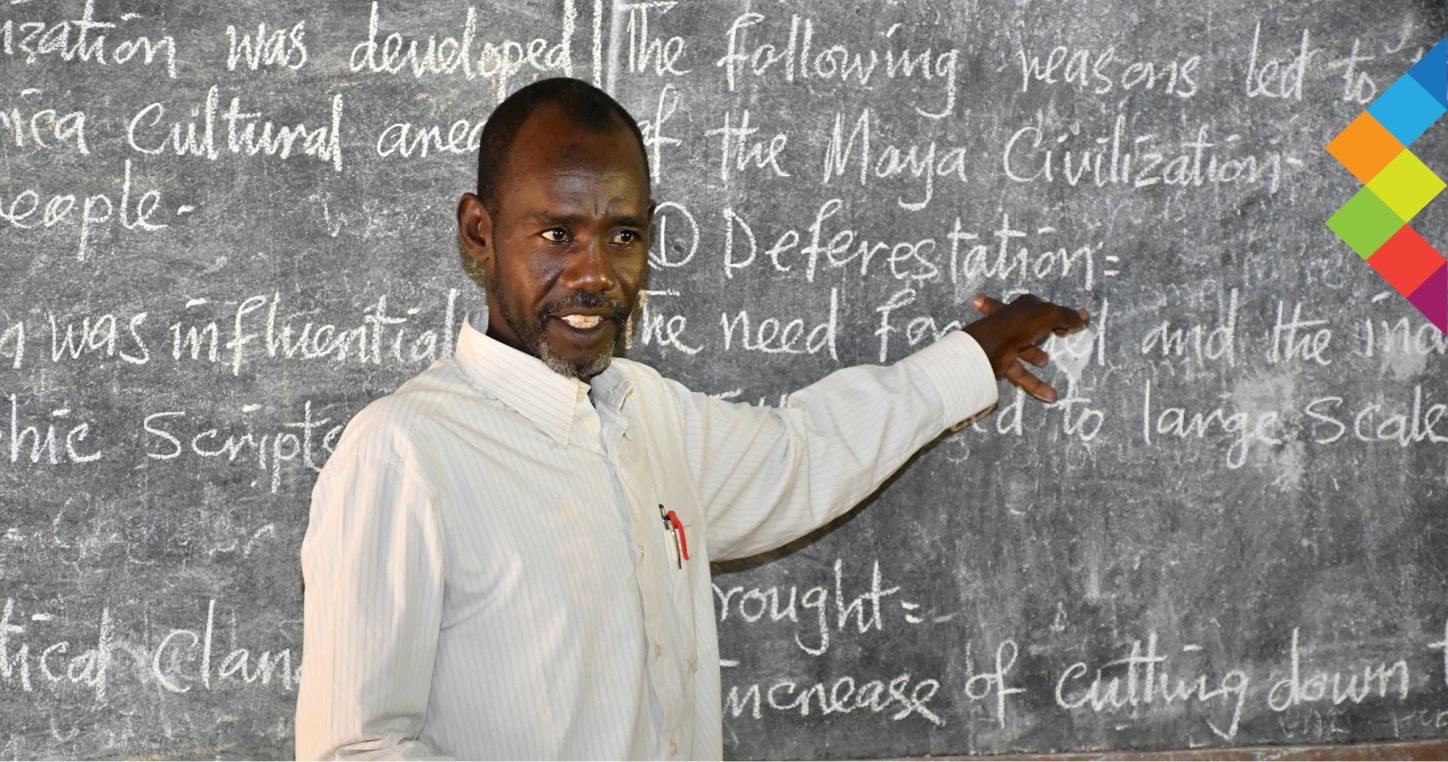

Teachers in South Sudan are the foundation of the education system, providing critical support in one of the most challenging environments globally. Despite their indispensable role, they face widespread financial instability, chronic delays in salary payments, and wages that are far below a livable standard. These issues destabilize the education system, contributing to teacher attrition, absenteeism, and diminished student outcomes, further compounding the country’s education crisis.

A new study examines the current state of teacher compensation in South Sudan, assessing its adequacy in meeting teachers’ needs and its effectiveness in maintaining long-term educational stability. The study—conducted by a team of researchers from Education Action in Crisis (EAC) and the Center for African Education at Teachers College, Columbia University, and commissioned by Education International—aims to describe the existing payment structures for different teacher profiles, highlight key challenges, and explore potential solutions to address teacher salary payment challenges in the region. Additionally, the report explores governance strategies to address systemic barriers to teacher retention and performance.

South Sudan: a nation in crisis

South Sudan’s education system is shaped by overlapping crises, including ongoing conflict, displacement, and severe economic instability. These challenges significantly impact teachers and their ability to deliver quality education. As of December 2024:

- 76% of the population requires humanitarian assistance;

- 7.1 million people face acute hunger;

- 1,281 schools were forced to close due to teacher shortages, conflict, and lack of students.

Of the country’s teaching workforce:

- 37% are volunteers;

- 37.4% lack formal qualifications;

- Only 30% of teachers are on the government payroll.

These gaps have profound consequences. Teachers often go months without pay, leading to demotivation, absenteeism, and burnout. Many leave the profession entirely or seek alternative employment to support their families, creating further instability in the education system.

The failure to address these systemic issues reflects a broken social contract between the government and its teachers. This social contract—the implicit agreement that teachers provide a vital public service in exchange for fair compensation and support—has been neglected. By failing to deliver on its obligations, the state undermines trust and erodes the very foundation of its education system, perpetuating cycles of poverty and instability.

A system under strain

South Sudan’s teacher compensation system is fragmented and poorly equipped to meet the needs of its educators. Payment structures fall into three main categories, each with unique challenges:

1. Government teachers

Government-employed teachers are paid through the national payroll system, based on official salary scales. However, delays and irregular payments are common due to financial constraints and administrative inefficiencies. Many government teachers must seek additional work to supplement their income.

- Official monthly rate: SSP 9,512–167,712 (approximately $3–58)

- Range reported by teachers: SSP 15,000–100,000 (approximately $5–35)

2. Volunteer teachers

Volunteer teachers, often employed in crisis-affected areas, are contracted by NGOs or humanitarian partners. These teachers receive stipends or incentives rather than salaries, with compensation tied to short-term projects. Payments are inconsistent, and volunteers often earn significantly less than government teachers, making it difficult for them to sustain their work.

- Standard incentive: $40 per month (Education Cluster determination)

3. Incentive teachers

In refugee settlements, incentive teachers—who are often refugees themselves—are funded by organizations such as UNHCR and NGOs. They receive cash stipends and in-kind support. Payments are linked to humanitarian programming cycles, and many incentive teachers lack formal recognition of their qualifications. Interestingly, in South Sudan, refugee teachers are paid significantly more than their national counterparts, albeit still falling short of a livable wage.

- Standard range: $100–150 per month (teachers), $250 (head teachers)

- Reported range: $40–500

The human cost of underinvestment

Teachers in South Sudan face significant financial challenges that affect both their professional performance and personal well-being. Many struggle to afford basic necessities, support their families, or save for emergencies.

For instance, Nyawira Ladu [1], a volunteer teacher in a refugee settlement, earns just $300 after taxes. With two children studying in Uganda, her salary barely covers their school fees, forcing her to borrow money to make ends meet. Despite teaching for over a decade, Nyawira is unable to escape financial stress or invest in her own professional development.

This financial instability directly impacts teacher motivation and retention. Without reliable pay, teachers are less likely to prepare lessons, attend classes consistently, or stay in the profession long-term. Students bear the consequences as underprepared and frequently absent teachers struggle to provide stable, nurturing learning environments. This creates a ripple effect throughout communities, denying children the opportunities needed to secure brighter futures and often pushing them toward dropping out.

This fragmented system reflects deeper governance failures. The inability to provide consistent, fair compensation to teachers exemplifies the breakdown of institutional trust—a hallmark of the broken social contract. This lack of trust discourages teachers from investing in their profession, weakening the overall education system and contributing to its collapse. These challenges represent more than just logistical issues—they signal the moral and structural failure of a social contract that should prioritize the well-being of educators and students alike.

A path forward: turning insights into action

This study outlines practical, actionable strategies to tackle South Sudan's teacher compensation challenges, paving the way for sustainable improvements in education.

1. Increase funding for education

Address resource shortages by securing stronger financial commitments from both the government and international donors. Prioritize teacher compensation as a cornerstone of educational development.

2. Streamline payroll systems

Overhaul inefficient bureaucratic processes to reduce salary delays. Implementing digital payment systems can ensure consistent and reliable compensation.

3. Revalue the teaching profession

Enhance the social and financial status of teachers by recognizing their contributions. Offer opportunities for professional development to improve retention rates and attract new talent to the profession.

Recommendations

To address systemic challenges and align with the needs of various teacher profiles—government-paid, cluster partner-supported, and UNHCR-supported—this study recommends a multi-pronged approach:

Reconciliation of salary arrears

- Clear outstanding salaries for teachers on the government payroll.

- Improve coordination between the Ministry of General Education and Instruction (MoGEI), the Ministry of Finance and Planning (MoFP), and donors to ensure salary arrears are distributed effectively.

Immediate interventions

- For government-paid teachers: Resume payments promptly and progressively increase wages to a living standard.

- For cluster partner-supported teachers: Harmonize wages across implementing partners and ensure timely monthly payments, adjusting for inflation.

- For UNHCR-supported teachers: Provide consistent wages aligned with experience and qualifications and establish mechanisms for salary harmonization across sectors.

- Implement pension and insurance programs across all profiles to enhance financial security.

- Streamline digital and manual payment systems to ensure equitable and timely salary disbursements.

Long-term solutions

- For all teacher profiles: Develop an Education Management Information System (EMIS) and Refugee Education Management Information System (REMIS) to track payroll, qualifications, and placements.

- For volunteer and refugee teachers: Expand certification pathways, allowing experienced teachers to formalize their roles and integrate into government systems.

- For unionized teachers: Strengthen the teachers’ union and facilitate broader stakeholder collaboration to optimize resources, advocate for teachers’ needs, and build long-term sustainability.

These targeted strategies aim to build a resilient and inclusive compensation system that supports the diverse needs of South Sudan's teachers.

Investing in teachers to rebuild South Sudan

The broken social contract between South Sudan’s government and its teachers (among other civil servants) has undermined the stability of the education system. Teachers are the cornerstone of South Sudan’s education system, yet the current compensation structures fail to support them adequately. Addressing salary arrears, harmonizing pay systems, and strengthening governance are essential to restoring trust and stability.

By prioritizing teacher well-being, South Sudan can rebuild this critical social contract, creating a resilient and thriving education system. This study offers a roadmap for systemic reform, ensuring teachers are supported, motivated, and empowered to fulfill their roles. Investing in teachers is not only a moral obligation but a crucial step toward rebuilding the nation’s future.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.